Burin engraving

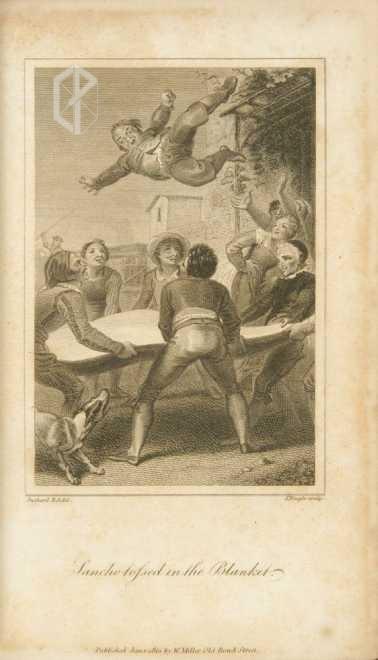

It is remarkable the bulk of the figures and how Stothard has tried to represent different gestures (effort of the figures blanketing Sancho) and how he has tried to recreate a Spanish setting (with "goyescas" clothes).

The engraving is not too much agile; Sancho's frightened face is forced.

Thomas Stothard (London, 1755 – London, 1834): History and portrait painter and acquafortist. He was apprenticed to a draughtsman of patterns for brocaded silks, and during his spare time he attempted illustrations for the works of his favorite poets. In 1778, he became a student of the Royal Academy, of which he was elected associate in 1792 and full academician in 1794. In 1812 he was appointed librarian, having served as assistant for two years. He designed plates for pocket-books, tickets for concerts, illustrations to almanacs and portraits of popular actors. Among his more important series are the two sets of illustrations to “Robinson Crusoe”, one for the “New Magazine” and one for Stockdale's edition, and the plates to “The Pilgrim's Progress” (1788), to Harding's edition of Goldsmith's “Vicar of Wakefield” (1792), to “The Rape of the Lock” (1798), to the works of Solomon Gessner (1802), to William Cowper's “Poems” (1825), and to “The Decameron”; while his figure-subjects in the superb editions of Samuel Rogers's “Italy” (1830) and “Poems”(1834) prove that even in old age his imagination was still fertile, and his hand firm (Benezit IX, 854 – 855).